- The early days of comparative anatomy

- Cambridge's Veterinary School

- The 1960s

- From the 1970 to the late 1980s

- From the late 1980s to the 1990s

- From the 2000s to current days

The early days of comparative anatomy

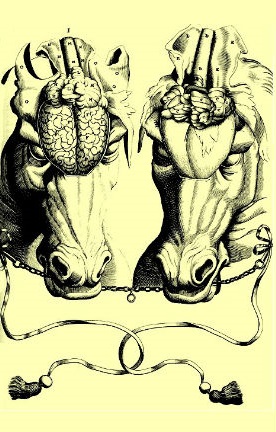

Comparative anatomy has a long and noble history. Claudius Galen’s second century studies of animal brains in On the Usefulness of Parts of the Body paved the way for modern neuroscience. In the seventeenth century,

William Harvey (a Cambridge medical graduate) developed his famous theory of the circulation of the blood based largely on a description of the one-way valves in the heart in an earlier veterinary text by the Italian Carlo Ruini: Anatomia del Cavallo (Anatomy of the Horse). And in the nineteenth century, comparative morphology was central to the debates about the interplay between embryonic development and species evolution that continue to this day - see, for example, Ernst Haeckel’s Generelle Morphologie der Organismen.

Yet veterinary anatomy - the dedicated study of the structure of the major domestic species - gained momentum rather more slowly, as the veterinary profession developed in Britain and around the world. Although usually directed at training future clinicians, Cambridge’s scientific ethos has meant that the subject has here always had strong roots in developmental and evolutionary biology. We often wonder how medical students cope ‘without anything with which to compare’ their target species.

Cambridge's Veterinary School

Although Cambridge is the third oldest extant university in Europe, its veterinary school is relatively young, having started in earnest in 1949 with the intake of a grand total of eight veterinary undergraduates.

Forerunners of the Vet School included a large animal disease research station established by the Department of Pathology in 1909, and a pre-clinical veterinary course starting in 1935 - the latter consisting of an only-slightly-modified Natural Sciences course which qualified its graduates to carry out their clinical training at another veterinary school.

Although plans were in place some years earlier, in 1949 the Professor of Zoology, Sir James Gray, created the first University Demonstratorship in Veterinary Anatomy to support the new veterinary course. The appointee was Reg Green, who was to dominate the development of Veterinary Anatomy in Cambridge for three decades.

Veterinary Anatomy was very much a Cinderella subject at first. It was planned as an additional part of the second year Mammalian Zoology course, but prospective vets had to cram the course into the summer vacation between their first and second years. The burdens on the students were great and the decades since have been a continuing story of trying to reduce this load as much as possible - unlike most students, veterinary students must spend many weeks of the university vacations gaining extramural experience.

As part of the Department of Zoology, Veterinary Anatomy was housed on one side of the Zoology courtyard, although its tenure there was to be brief. After some internal wrangling, it was decided in the 1950s that the discipline was to flee the nest of its mother-department and be established in its own purpose-built building. By coincidence, the only appropriate available plot was next to the Department of Anatomy, and the head of that department agreed to the proximity of the veterinary interlopers as long as he was "in no way bothered".

Reg Green was instrumental in the design and management of the new building programme and in 1958 thirty students boldly strode through the doors of what is still the hub of veterinary anatomy teaching at Cambridge.

The 1960s

The new building contained a purpose-built dissection room, embalming room, museum, library, lecture theatre and offices. Many of these are still in use today, albeit in renovated form, although the adjacent Anatomy Department often encroached into this veterinary-dedicated sanctum. At the time of the move, the newly inaugurated Sub-Department of Veterinary Anatomy employed five teaching officers and fourteen assistant staff, with Reg Green as its ‘Deputy Director’. The tradition of long-serving, dedicated staff was also becoming well established - for example, Roger Akester was to teach in the Sub-Department from 1959 to 1991.

The 1960s saw the start of a gradual freeing of veterinary students from studying human anatomy. Just as the veterinary course had been seen as an ‘add-on’ to Zoology, so was it initially viewed by Anatomy. However, the vets were soon spared the experience of human dissections, and their lectures also gradually diverged from those delivered to the medics. The establishment of the Medical Sciences Tripos in 1965 allowed another rethink of the veterinary curriculum and Veterinary Anatomy slowly became a subject in its own right instead of a curricular afterthought.

A thriving, vibrant intellectual atmosphere pervaded Veterinary Anatomy. Staff and students were constantly re-evaluating what they discovered in the dissections. Typical of this was Reg Green’s re-analysis of the functions of muscles - a simpler system than is available in any text book, elements of which are still taught at Cambridge to this day. Other advances included a greater understanding of the development of the ruminant stomach, the morphological variations in the mammalian placenta and respiration in birds.

Several of the teaching staff were to use their time in the Sub-Department as a springboard to illustrious careers. Ian Silver (taught until 1970) was to take up a chair at Bristol, Barry Cross (taught until 1967) was to become Head of the Babraham Institute and Alan Findlay (student from 1958, taught 1967-1970) became a stalwart of the Cambridge Physiological Laboratory and Senior Tutor of Churchill College.

From the 1970 to the late 1980s

In the 1970s the Sub-Department continued to thrive and student numbers gradually increased to around forty, mirroring the success of the Vet School. In 1975, the Departments of Animal Health and Veterinary Clinical Studies merged to form the Department of Clinical Veterinary Medicine at the site on Madingley Road (although the word ‘Clinical’ was dropped from the name in 2004).

In the 1970s the Sub-Department continued to thrive and student numbers gradually increased to around forty, mirroring the success of the Vet School. In 1975, the Departments of Animal Health and Veterinary Clinical Studies merged to form the Department of Clinical Veterinary Medicine at the site on Madingley Road (although the word ‘Clinical’ was dropped from the name in 2004).

Back in the centre of Cambridge, this decade also saw the appointment of yet more long-standing members of staff. David Chivers (student from 1963, taught 1970-present) is a primatologist active in conservation, and was also appointed to Veterinary Anatomy’s first Readership. The Reverend Jonathan Holmes (student from 1967, taught 1977-present) is now Dean of Queens’ College chapel. John Brackenbury (taught 1984-present) is a zoologist with particular interests in animal locomotion and exercise.

Over the years we have also been fortunate to be assisted (i.e. organised) by a series of excellent technicians, some also extremely longstanding (longsuffering?), including Geoff Hopkins, Ian Edgar, John Holder and Roger Tattersall.

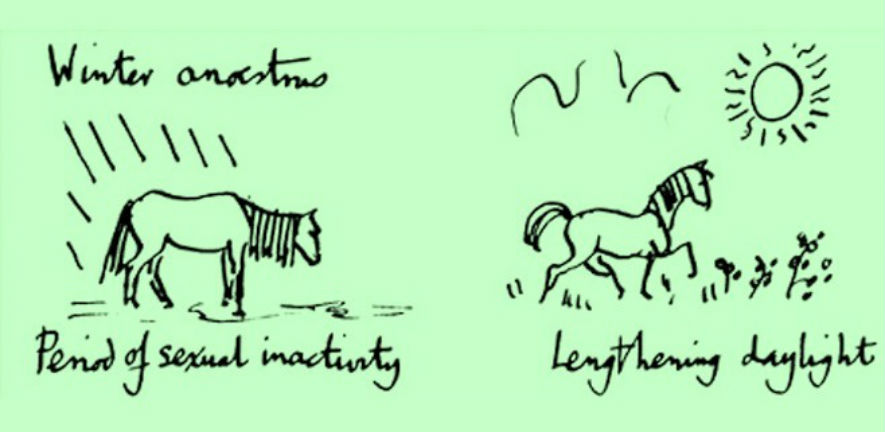

After a spectacularly long tenure at the helm, Reg Green retired in 1983 and Donald Steven was appointed ‘Director’ - a student at Cambridge from 1954, he had started teaching in Veterinary Anatomy in 1961. Steven was an explorer of that most diverse mammalian organ, the placenta, and his research and teaching were both leavened by his wit and endearingly clear pen and ink drawings. This author was a student during the Steven era and selected the above image as his own personal favourite example of Steven’s opus.

From the late 1980s to the 1990s

The late 1980s brought considerable uncertainty for Veterinary Anatomy, as well as the Vet School. The Riley Report on veterinary education in the UK was published in 1988 and it recommended that two of the six schools be closed - selecting Cambridge and Glasgow for annihilation. There was considerable uproar at this recommendation, including protests by the great and the good, as well as students of the day. Unusually for the government of that time, this external pressure seemed to achieve its aim and the veterinary course at Cambridge was saved. This was fortunate for all concerned, as veterinary student numbers in the UK have increased dramatically ever since.

The late 1980s brought considerable uncertainty for Veterinary Anatomy, as well as the Vet School. The Riley Report on veterinary education in the UK was published in 1988 and it recommended that two of the six schools be closed - selecting Cambridge and Glasgow for annihilation. There was considerable uproar at this recommendation, including protests by the great and the good, as well as students of the day. Unusually for the government of that time, this external pressure seemed to achieve its aim and the veterinary course at Cambridge was saved. This was fortunate for all concerned, as veterinary student numbers in the UK have increased dramatically ever since.

There were also problems closer to home. Donald Steven was becoming increasingly ill, and had to leave his post in 1990. His place was temporarily taken by another placental biologist, Graham Burton (taught 1978-1991, still active in the department).

As ‘Acting Director’, Burton had to steer Veterinary Anatomy through some troubled waters. The ethos and practice of university funding was changing and departments’ financial stability was depending more and more on their research output and less on their teaching. Yet Cambridge realised that, whatever the prevailing regime, teaching remained the raison d’être of a University. In 1993 the status of Veterinary Anatomy was to change greatly. The sub-department was merged with the Department of Anatomy and the number of ring-fenced teaching staff in Veterinary Anatomy was reduced.

However, to counterbalance these changes, a new position of University Clinical Veterinary Anatomist was created. This was a post dedicated to organising the teaching of veterinary anatomy to undergraduates, and delivering of much of that teaching. The intention was that the post would be filled by someone with clinical experience, able to enthuse students about the practical relevance of the material they were learning.

In 1993, the first appointee to this role was John Grandage, a famously affable chap who had previously taught in Australia. He introduced a renewed sense of clinical relevance to the course, and also oversaw the redesign of veterinary pre-clinical subjects that took place in the 1990s. From this point onwards, first-year students would study a course in Veterinary Anatomy and Physiology (although the former greatly outweighed the latter) and in the second year they would study separate courses in neuroanatomy, reproductive biology and comparative vertebrate biology.

Pressures on the timetable were great and Grandage ‘fought his corner’ for veterinary anatomy and also efficiently organised the time he was allocated. Along with other staff, he was also actively engaged with the Vet School in the development of the veterinary curriculum as a whole. For example, he drove the increased use of radiography as a bridge between anatomy and the clinical course.

From the 2000s to current days

Grandage returned to Australia in 2002 and the following year saw the appointment of the second, and current, University Clinical Veterinary Anatomist, David Bainbridge. Himself a student in the Department from 1986, Bainbridge’s subsequent career interest had been (at the risk of repetition) the biology of early pregnancy and placentation. He had heard of the vacancy when invited back to Cambridge to speak at a Festschrift meeting to celebrate the work of Donald Steven.

Grandage returned to Australia in 2002 and the following year saw the appointment of the second, and current, University Clinical Veterinary Anatomist, David Bainbridge. Himself a student in the Department from 1986, Bainbridge’s subsequent career interest had been (at the risk of repetition) the biology of early pregnancy and placentation. He had heard of the vacancy when invited back to Cambridge to speak at a Festschrift meeting to celebrate the work of Donald Steven.

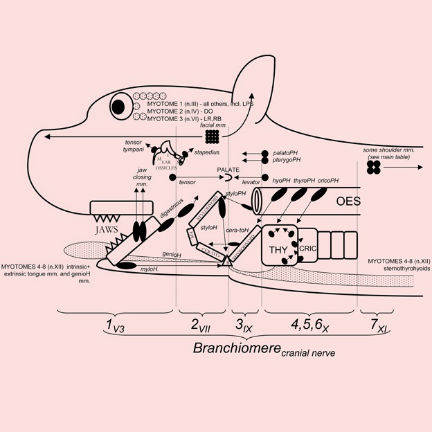

Since that time the course has developed further. The evolutionary, developmental and biomechanical underpinnings of veterinary anatomy are stressed yet further, and are increasing linked to areas of clinical importance. The students now receive an introduction to ultrasound and MRI, and get the chance to interpret these newer modes of diagnostic imaging. Dissection remains the core of the course, however, and dissection of large hoofed mammals has been given new impetus by the transfer of entire sessions to the new post mortem room at Madingley Road. ‘Live Anatomy’, in which students are able to apply what they have learnt in dissection to living, breathing animals has also become a central part of the course. Time has even been freed for a new course in the second year, dedicated to that most complex anatomical construct, the vertebrate head.

With his background in reproductive biology, Bainbridge now also organises the Veterinary Reproductive Biology course - an integrated course in anatomy and physiology. In an ironic but intellectually rewarding reversal of the ‘escape from Natural Sciences’ in the1950s, this course is now shared with Natural Sciences students.

At the start of 2006, the Departments of Anatomy and Physiology merged to create the descriptive, if magniloquent, Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience. We believe that this change will be good for what is now called the ‘Veterinary Anatomy Programme’. The combined department is now the major partner in undergraduate veterinary teaching, and the Physiology Department has brought with it many staff inherently sympathetic to all things veterinary.

Veterinary Anatomy remains a small but important element of the Cambridge mix. As a small subject it is important to make ourselves heard throughout the university. However, our small size - we teach around seventy students each year - is also our greatest advantage. We are, for example, extremely responsive to student opinion. The atmosphere is cheerful, sociable and sometimes even irreverent, and we believe that the veterinary students see us as their ‘spiritual home’ during their pre-clinical years. Who would have thought that dissection could be a social highlight of the student week? We continually strive to teach what is important and what is interesting, while supporting the aim that veterinary graduates should be able to cope with anything thrown at them. Most of all, we try to foster the sense of inquiry, independence and good humour essential for students destined for such a prestigious and responsible career.

Written by David Bainbridge, and based on written material by Reg Green (up to 1970) and the reminiscences of other veterinary anatomy teaching staff (after 1970). Please contact David Bainbridge if you feel that anything is wrong, or if you can add anything to our archives.