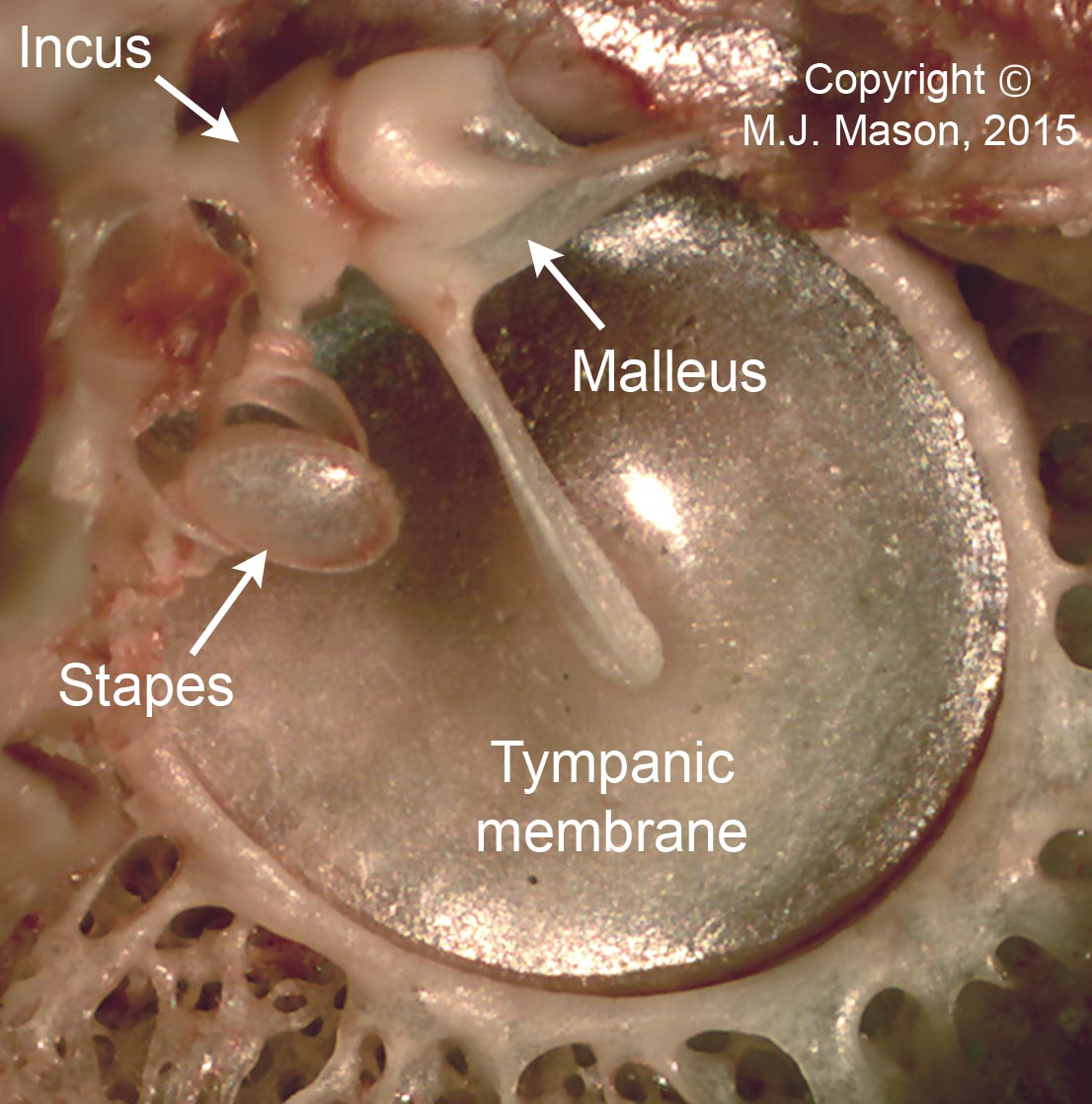

In mammals, vibrations of the tympanic membrane are transferred to the inner ear by means of three auditory ossicles, the malleus, incus, and stapes (meaning "hammer", "anvil" and "stirrup": see Fig. 1). Although people tend to refer to 'the' mammalian middle ear, in fact the morphology of the ossicles and other auditory structures differs considerably between different groups. These differences are of important physiological and ecological significance since they will help to determine what an animal hears.

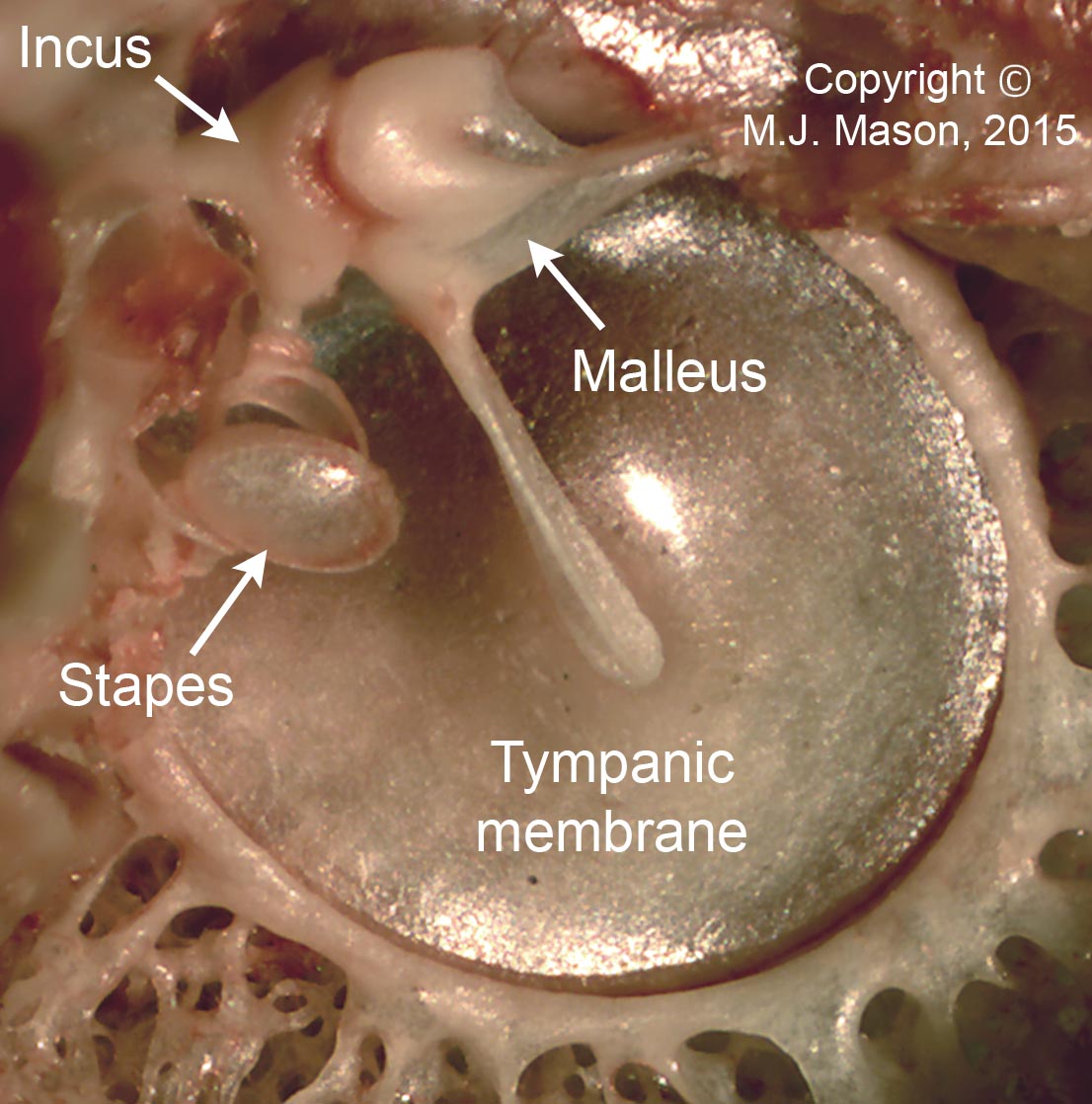

One might expect that animals living in unusual environments would have unusual ear adaptations. This is indeed the case in subterranean mammals such as moles, mole-rats and golden moles, which have formed a key focus of my studies. For example, some have middle ear cavities which connect with each other through the middle of the skull, while others have missing muscles or massive mallei. Although many people are interested in whether airborne hearing in these curious animals is tuned to the low frequencies which propagate best through tunnels underground, subterranean mammals can in principle also use seismic vibrations, which travel well through soil or sand, to gain information about prey species, microhabitat or approaching predators (Mason & Narins, 2010). Those species which generate their own seismic signals by thumping might use substrate vibrations to subserve intraspecific communication or even, perhaps, seismic echolocation. In the golden moles (Chrysochloridae) of sub-Saharan Africa, the malleus can be enormously enlarged and composed of unusually dense bone (Mason, 2003a, Mason et al., 2006; Fig. 2). These bizarre bones seem to be adapted towards the transmission of low-frequency seismic vibrations, via a mechanism referred to as inertial bone conduction (Mason, 2003b). Field-work that I participated in suggests that the desert golden mole Eremitalpa granti uses its enlarged ossicles to detect vibrations generated as wind blows through tussocks of dune grass, where its prey species live (Lewis et al., 2006). I have recently been investigating the ears of one of the most peculiar animals on the planet - the naked mole-rat (Mason et al., 2016)!

By looking at the diversity of ear types found among mammals, we can address the important question of to what extent model species are actually representative of mammals in general and humans in particular. For example, unlike humans, mice and rats have microtype ear ossicles which feature a large orbicular apophysis, a lump of bone which increases their mass and moment of inertia. This structure has previously been misidentifed as the "processus brevis" in developmental studies, which have drawn attention to its derivation from the second branchial arch (see Mason, 2013). Perhaps this mistake was made because researchers are more used to looking at human ear bones, which lack the apophysis! Bats and shrews also have microtype middle ears, and I have collaborated with Prof. Brock Fenton's group in Canada regarding bat ears (Veselka et al., 2010) and Prof. Ilya Volodin's group in Moscow which works on shrews (Zaytseva et al., 2015).

Guinea pigs and chinchillas, commonly used as study animals in hearing research, have particularly unusual middle ears featuring fused ossicles, reduced or missing muscles and synovial stapedio-vestibular articulations (Mason, 2013). I have called this the "Ctenohystrica type" ear, referring to the wider group to which these mammals belong. The unique features of the Ctenohystrica type ear may collectively improve low-frequency hearing. In fact, there is a surprising diversity of ear types among rodents, which I have summarized in a recent book chapter (Mason, 2015).

| Fig. 1: Internal view of the mammalian middle ear apparatus. The stapes footplate, projecting towards the viewer, would normally be contained within the oval window, the entrance to the inner ear. | |

| Fig. 2: Rotating radiograph of the skull of a golden mole, Eremitalpa granti granti. Note the enormously enlarged mallei, which appear as rounded, white masses in each ear (see Mason, 2003). |